As he recently dug into an unfamiliar drama, California native Adan Franco relied on the closed captioning at the bottom of his TV screen to help make sense of the characters and their foreign argot.

The show was “The Sopranos.”

“I had to pay close attention and internalize all this fast-paced information, especially in the first episodes,” so the transcription was critical, says the 24-year-old musician.

It isn’t just New Jersey accents and mob lingo that benefit from translation. Mr. Franco says he almost always keeps captioning turned on, no matter what’s playing. “It’s just my preferred way of watching things,” he says.

Subtitles have always been required reading for people watching foreign-language films. And for deaf and hard-of-hearing audiences, captioning is vital to any screen experience involving sound.

Because the primary purpose of closed captioning is accessibility—as required by federal law since the 1990s—it also includes sonic elements other than dialogue, such as song lyrics and sound descriptions like [ominous rustling] or [soothing music]. Subtitles are translations of dialogue into a different language.

In the sci-fi series ‘The Expanse,’ captions spell out the patois of people known as Belters.

PHOTO: AMAZON PRIME VIDEO

Some of the people most committed to captioning don’t need it at all. They are viewers who hear just fine but prefer to read along with everything they watch, including TV shows and movies in their own language, as a hack to better understand what is happening on screen.

It is a subculture of sub-text that veterans of the captioning industry say is growing. Driving the habit: the multitasking ways of younger viewers, and the broader influence of phones and other personal screens that overflow with captioned imagery, from internet memes to video clips that spread on social media.

“It’s a generational change,” says Larry Goldberg, who helped write federal legislation mandating closed-captioning in digital media and is the current head of accessibility at Verizon Media. Most producers and distributors no longer have to be prodded to include captioning, largely because of demand from viewers for whom it is entirely optional, he says. “It’s gone mainstream, and when I started in this business, I would never have imagined this,” he says.

Emily Boudrot, a student at Ball State University in Indiana, got into the caption habit in high school because it was frustrating to rewind when she missed things. Her mother hates it when she turns on the captions at home, but she has converted others to the written word. “Most of my friends use them,” she says. “And if they didn’t before, they do now after spending time with me.”

Actors who mumble, whisper or talk over each other? Programs with wildly fluctuating sound levels? Knotty dialect from the old-time British gangsters of “Peaky Blinders”? The lyrics to a song underscoring a dramatic scene? Captioning helps you capture it all, adherents say.

Some English speakers need help with the knotty dialect from the old-time British gangsters of ‘Peaky Blinders.’

PHOTO: NETFLIX

Off-screen, captions preserve domestic tranquility when dealing with a sleeping or noisy family member nearby. And they help viewers pick up on crucial dialogue even while chowing down on crunchy snacks.

“I felt like the captions and the audio were competing, and my brain didn’t know which one to follow,” she says.

Three years later, the romance is over, but Ms. Peters is committed to captioning. It not only helps her make out the accents of denizens of an asteroid belt in “The Expanse” (which she also stuck with), the university lecturer and sci-fi filmmaker says it brings out the nuances in her viewing across the board. “It’s just a part of watching scripted entertainment,” says Ms. Peters, who has been known to enable captioning on the TV sets of family members she visits.

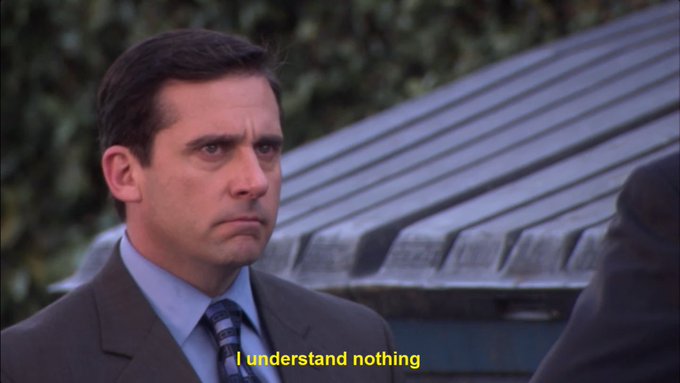

Some jokes in “Frasier” just seem funnier, some “Star Trek” lines more relevant, when reinforced in writing on screen, says Hannah Broder of Baltimore. She was introduced to closed captions in college through a friend who was hard of hearing. Now, “it just helps me take in everything I watch, even if it’s an episode of ‘The Office’ or ‘Parks and Recreation,’ ” says the 22-year-old social-media manager.

For many viewers who grew up watching subtitled Japanese anime series and scanning captioned clips on devices with the sound off, reading something on Netflix comes naturally.

“You’re watching a show but also doing two other things at the same time,” says Steve Howze, a 33-year-old sketch-comedy writer living in New York. He counts himself as a captions-on guy—except with comedies, he says, because the text often outpaces and spoils the punch lines.

More people are viewing TV and movies through the lens of social media, where screenshots and GIFs superimposed with text are ubiquitous. “When I watch things with the captions, I can just take a picture of the screen and have an instant meme,” says Nick Gilyard Spence.

Dominic Spence, left, and Nick Gilyard Spence bonded years ago over captioning.

PHOTO: JULIA ZAHAROVA

For the 28-year-old Miami publicist, text on a TV screen also announced true love. Mr. Spence and a former high-school acquaintance discovered they both loved watching the 2000s sitcom “Girlfriends”—and with captioning turned on. “I thought, ‘We are soul mates,’ but I didn’t say that out loud because it was only our second date.”

Since then, the couple has used captioning to process the dense soliloquies of “Scandal,” the murmured remarks in “The Real Housewives of Atlanta” and the chaotic exchanges in the 2011 movie “Contagion.” They even incorporated the technology into their 2017 wedding ceremony. “I vow to love you without ceasing,” Nick said to his now-husband Dominic Spence, “and turn on the closed captions when we watch our favorite movies.”

Write to John Jurgensen at john.jurgensen@wsj.com